Learning Theory: Constructivism

Exploration of constructivism, which includes concepts such as the zone of proximal development, scaffolding, and motivation. Keller's ARCS model and social constructivism are explored and applied to instructional design.

Overview of Constructivism

Constructivism is a learning theory that challenges the idea of passive knowledge transfer. Instead of viewing learning as the delivery of content, constructivism sees it as an active process where learners build understanding through experience, reflection, and interaction. Knowledge is not transmitted,it is constructed by the learner, shaped by their prior knowledge, beliefs, and the context in which learning happens.

This approach places the learner at the center of the experience. Meaning is not fixed or objective; it's created as learners engage in authentic tasks, ask questions, test ideas, and draw conclusions. Instruction is not about control, it's about creating conditions for learners to explore, problem-solve, and develop their own understanding.

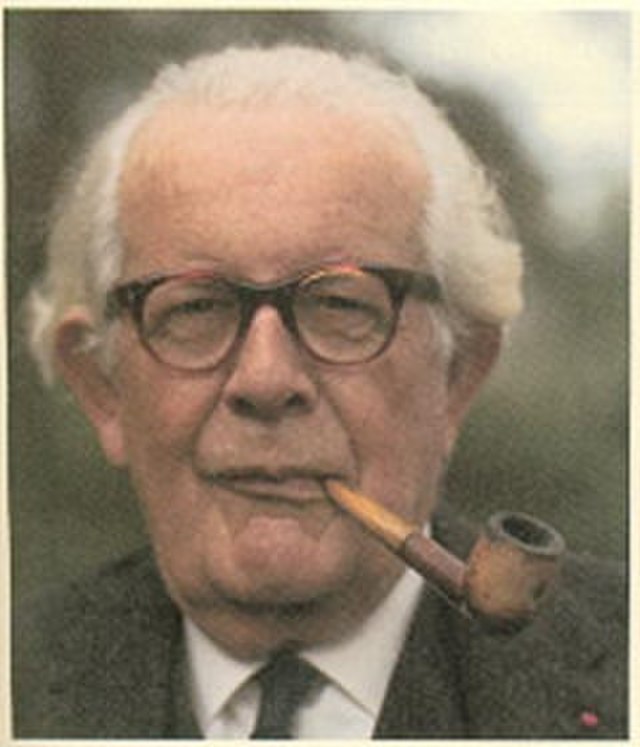

Two key figures helped shape constructivism:

- Jean Piaget (1936)

Introduced the Theory of Cognitive Development, explaining how learners assimilate new information and accommodate it into existing mental structures (schemas). He emphasised the importance of cognitive conflict, the tension between what a learner already knows and what they encounter, as the driver of learning. Resolving this conflict restores cognitive equilibrium and deepens understanding. - Lev Vygotsky (1978)

Expanded the theory by adding a social dimension. His concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and emphasis on scaffolding showed that learning is most effective when guided by more knowledgeable peers or mentors. This laid the foundation for social constructivism, where knowledge is co-constructed through meaningful interaction and collaboration.

Constructivism informs a wide range of practices today, including project-based learning, inquiry models, and collaborative problem-solving. Rather than delivering content, instructors create environments where learners can explore, connect ideas, and develop understanding through meaningful engagement.

Social constructivism builds on this by emphasizing the importance of learning through interaction. When learners collaborate, explain their thinking, challenge assumptions, and respond to feedback, they don't just share knowledge, they help construct it together. Strategies like peer-to-peer dialogue, group problem-solving, and reciprocal teaching support this process by encouraging students to negotiate meaning, apply ideas in real contexts, and learn from each other. This approach turns classrooms and online spaces into communities of learning, where dialogue and collaboration are part of the instructional design.

"Constructivism isn't about delivering content. It's about designing environments where learners can explore, connect ideas, and build understanding through meaningful engagement"

Connections to teaching and learning

Constructivism changed how we think about learning by shifting the focus from delivering information to designing experiences. Instead of asking, "What content should I present?" we start asking, "What kind of task will help learners figure this out for themselves?"

In practice, that means giving learners the space to explore, question, and reflect. For example:

- When learners work through a case study or scenario, they're not just reviewing facts; they're testing ideas, revising their thinking, and building meaning in context.

- When a concept is introduced through a real-world challenge, learners are more likely to engage with the material and see its relevance.

Piaget's theory of cognitive development reminds us that learners build understanding by working through challenges that don't quite match what they already know. That's why it's useful to include tasks that provoke thought, rather than explain everything upfront.

Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) highlights the importance of support. Learners make more progress when we scaffold their experience, whether that's through modelling, peer interaction, or guiding questions built into the activity.

Together, these ideas push us to design instruction that gives learners room to think, struggle productively, and talk things through with others. It's not about leaving them to figure it out alone, it's about creating the right balance of independence, structure, and collaboration.

"Constructivism challenges us to design learning that feels real. It is less about content delivery, more about meaningful tasks, collaboration, and the thinking that happens in between"

Theory of Cognitive Development

Piaget's work shaped the foundation of constructivist thinking. He believed that learners actively construct knowledge by interacting with their environment, not by receiving it from someone else. His idea of cognitive conflict, the tension between what a learner already knows and what they experience, helps explain why we design tasks that challenge existing thinking.

Social Constructivism

Vygotsky shifted the focus of constructivism from individual discovery to social interaction. He argued that knowledge is co-constructed through dialogue, collaboration, and cultural context. Learning doesn't just happen inside the individual, it happens between people. Vygotsky's idea of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is central to constructivism. It shows how learning happens best when learners get just enough support to go beyond what they can do on their own.

Implications of Constructivism for Instructional (Learning) Design

Constructivism changes how I approach the design process. Instead of building content around what the instructor needs to say, I start with what the learner needs to experience in order to make sense of the concept. It's less about transferring knowledge, more about setting up the right kind of task, environment, or challenge so learners can build that knowledge for themselves.

In practice, this often means giving learners a problem to solve before I give them the full explanation. I'll use scenarios, case studies, or even simple prompts that require them to compare options, weigh decisions, or reflect on prior experience. The goal is to get them thinking before they're told.

Scaffolding is also a key part of this approach. Learners don't always get there on their own, and they shouldn't have to. Well-placed support, whether it's a worked example, a guiding question, or a peer conversation, can help them move from surface-level understanding to something deeper. This is where Vygotsky's ZPD really informs the design. The best learning happens just outside what the learner can currently do, with just enough help to push them forward.

I also think differently about success. With constructivism, it's not always about getting the "right" answer on the first try. It's about making progress, revising thinking, and showing evidence of learning through performance, reflection, or discussion. That has a big impact on how I structure feedback and assessment.

In short, constructivism helps me design for growth, not just accuracy. It encourages me to give learners space to engage, explore, and build meaning, not just absorb content.

Strengths and Limitations of Cognitivism

Corporate Training

Constructivism definitely has a place in corporate training, but like any approach, it works better in some situations than others. I've seen it add real value when the goal is to get people thinking, making decisions, or adapting to new challenges, not just following a script. But I've also had to adjust when time is short or when the business needs something more direct.

Strengths

- It's ideal for real-world problem solving. Scenario-based tasks and case studies help learners connect training to their day-to-day work.

- It supports deeper understanding. Instead of memorising rules, learners explore the why behind them, which helps with long-term retention and decision-making.

- It encourages active learning. By giving people space to reflect, share experiences, and test ideas, you end up with more engaged learners and richer conversations.

- It works well in collaborative environments, where learners can learn from each other, not just the content.

Limitations

- It can be time-intensive. In some cases, there just isn't room for discussion or exploration, especially in short compliance modules or quick refreshers.

- It's harder to scale and measure. Open-ended tasks don't always translate neatly into metrics, and outcomes may vary across learners.

- Some learners may find it too unstructured. Not everyone is comfortable with ambiguity, especially if they're expecting a clear, step-by-step format.

"Constructivism works best when the goal is understanding, not just compliance. It brings depth and engagement, but only when there's space for learners to think, apply, and explore.”

Scenario:

Handling Difficult Clients in Customer Service

As an instructional designer, I've created this scenario as a context-specific example where learners aren't just given answers, they actively learn by doing. It's built to reflect the core principles of constructivism: discovery, problem-solving, and experimentation. The goal isn't to memorise a script, but to help learners build judgment, empathy, and confidence in handling tough conversations, skills that only develop through realistic challenges and guided reflection.

Description

Learners are placed in a simulated live-chat role as a customer service representative. The customer is frustrated about being charged twice for a product and is demanding an immediate refund. As the chat unfolds, the learner must choose how to respond at key points: whether to apologize or explain, when to escalate to a supervisor, and how to manage tone and expectations.

The interaction includes:

- Customer frustration escalating when the learner gives vague or overly scripted responses.

- Opportunities to de-escalate by showing empathy, offering clear next steps, or validating the customer's concern.

- Reflection points after each response with targeted feedback and alternate approaches.

This design gives learners space to explore responses, test different approaches, and reflect on the outcomes, without real-world consequences. It's active learning through discovery, experimentation, and problem-solving, not just passive content delivery.

ZPD Skills Identified

These are skills that lie just beyond the learner's current ability to perform independently. With the right support, like examples, prompts, or guided reflection, learners can develop them over time:

- De-escalation techniques: Using language and tone that reduce tension rather than escalate conflict.

- Active listening in writing: Interpreting emotional cues in customer messages and responding in a way that shows understanding and empathy.

- Knowing when and how to escalate: Recognising the limits of one's role and responding appropriately without losing ownership of the issue.

Scaffolding and Social Constructivism Strategies

Scaffolding Strategy

To support learners as they develop the identified ZPD skills, I'd build in the following supports during the activity:

- Live coaching tips that pop up during the scenario (e.g. "Try validating their frustration before offering a solution") to guide decision-making in the moment.

- Modelled examples shown before the scenario, illustrating what an effective response looks like, along with commentary that explains why it works.

- Reflection prompts after each decision, encouraging learners to think critically about the impact of their choices and how they might improve.

These scaffolding strategies are designed to fade as learners gain confidence and internalise their judgment, keeping them supported, but not dependent.

Social Constructivism Approach

To encourage collaboration and knowledge construction among learners, I'd include a peer review activity after the simulation. Learners would be paired to review each other's response paths and discuss tone, timing, and escalation choices. They'd use simple guiding prompts like:

- "Which response felt most effective, and why?"

- "How might the customer have reacted differently if something else had been said?"

This type of peer interaction helps learners compare thinking, clarify their reasoning, and build deeper understanding through shared reflection.

Differentiation for Diverse Learners

Because learners bring different experiences, languages, and communication styles, I'd offer:

- Three simulation levels (basic, intermediate, advanced) to match learner confidence and familiarity.

- Optional coaching pop-ups, so learners who need more support can access it without disrupting others.

- Simplified or translated text options for learners working in a second language.

The aim is to keep the experience challenging but accessible, meeting learners where they are, while helping them stretch toward where they can go with the right support.

© Images from Wikimedia Commons in the public domain.